May is the most glorious month of the year. Flowers are blooming everywhere. Almost summer but not quite, there’s an expectant, magical quality to the passing of time. The scent of lilacs, the graceful drooping of tulips, a stand of irises or field of double-petaled poppies, as fragile and crinkled as crepe paper—all here for a brief moment, then gone. If you’ve been following In Hand for the last two years, you already know that we travel for gardens: Charleston, Villa Lante, Sacro Bosco, and of course, Vita Sackville-West’s beyond romantic white garden at Sissinghurst—the subject our first In Hand pilgrimage. We go for the stories, for the total work of art—but in the end, it’s the flowers themselves that fill our heads with beauty. As Vita once said— “Flowers really do intoxicate me.” Here, in honor of May and Vita and all the botanical artists who try to stop time / capture fleeting beauty, an ode to flowers in five parts—the perfect handful.

1. First and foremost, nothing elucidates this idea more than In Hand’s very own co-founder Lisa Borgnes Giramonti’s new watercolor series, Medieval Modern.

I conceived of the series after doing a deep dive one day into medieval illuminated manuscripts and stumbling upon a magnificent codex called The Voynich Manuscript which is written in a bizarre secret language no one has ever been able to crack, filled with drawings of mysterious plants never seen on this earth, and celestial maps of planets that don’t exist in our galaxy. To this day, the world’s best cryptographers and historians have no idea if the Voynich is real or fake, and there are books and videos dedicated to decoding it. I was especially entranced by the illustrations with their simple color palettes and slightly cartoonish naïveté. They had a strange life to them. Like the Voynich Manuscript, my botanical watercolors don’t exist on this earth, so I have free rein to paint whatever I like.

Every year, a new series or “volume" will be released. Right now, we’re still in Volume 1. Painted in watercolor on handmade Indian paper and sold exclusively at Nickey Kehoe (Los Angeles, New York, and online). Look book of designs coming soon, as the paintings tends to sell out immediately.

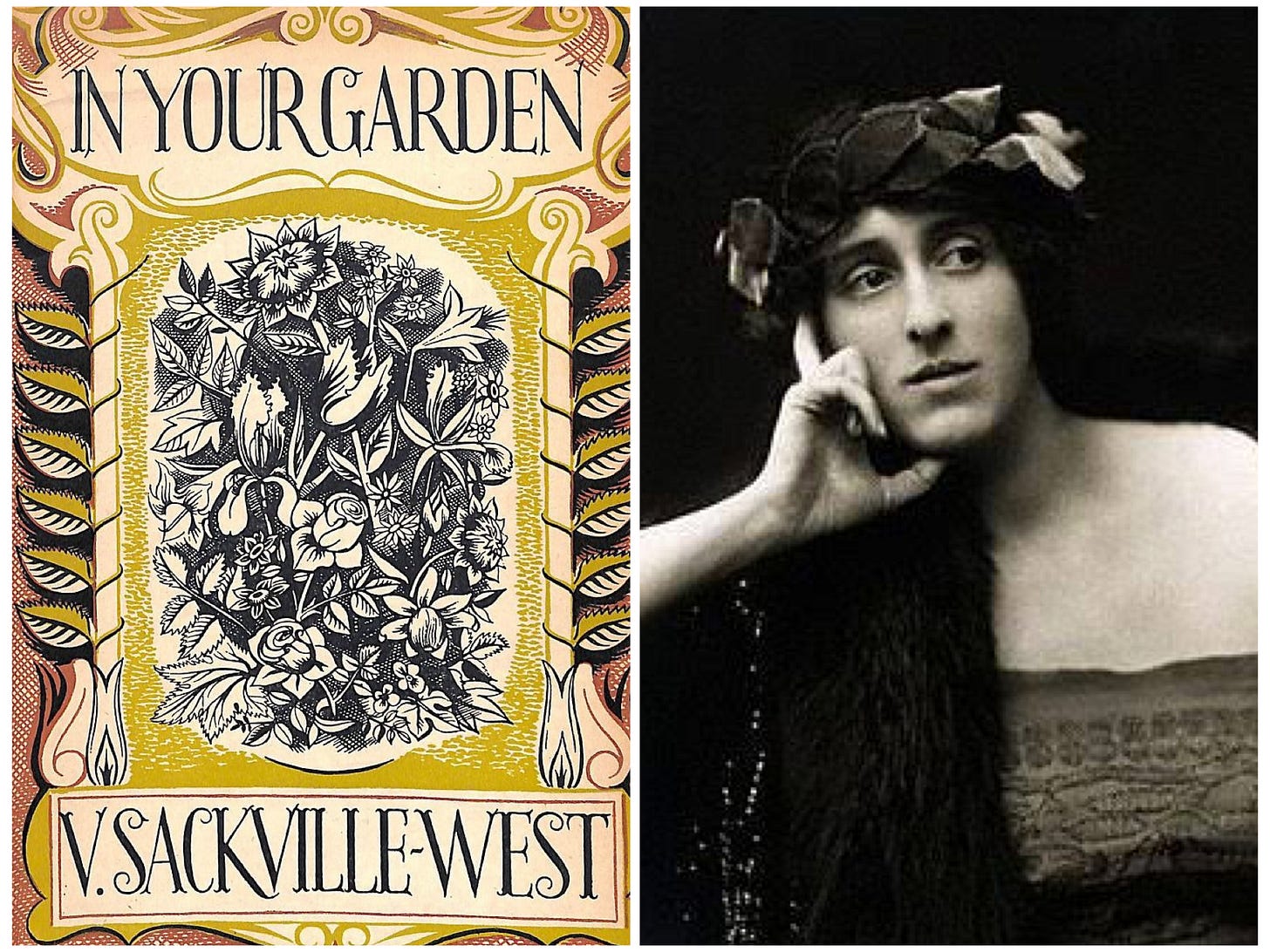

2. An over-the-top romantic/poet/gardener/writer/aristocrat and friend/lover of Virginia Woolf, Vita Sackville-West wrote prolifically about flowers and gardens, including my favorites In Your Garden and Some Flowers, which I prefer to digest by flipping open at random to a poetic description of a single flower. Repeat. I love that it’s not encyclopedic in its scope. “The flowers I have chosen depend chiefly on their loveliness of shape, colouring, marking or texture,” explains Sackville-West. “They are flowers which require to be looked at very intimately, if their queerness or beauty is to be closely appreciated. They are flowers which painters have delighted, or should delight, to paint.” She also wrote three additional books as part of the In Your Garden series, as well as Sissinghurst: The Creation of a Garden, Where the Old Roses Go, The Garden, and on and on.

3. The most staggeringly beautiful collection of glass flowers lives at the Harvard Museum of Natural History—a permanent display that includes 847 life-sized botanical models made by a father and son team of Czech glass artists. Commissioned in 1886 with the last model delivered in 1936, the work continued over an astonishing stretch of time— 50 years!!— sometimes part-time and other times with the family dedicating itself solely to this project (after an argument about them splitting production time with the zoology department making glass marine invertebrates). Leopold Blaschka and his son Rudolf worked on the glass flowers from their studio in Dresden, hand-crafting more than 4,300 models to represent 780 species of plants. I cannot fathom the extensive research and meticulous craftsmanship (even making their own glass) that went into these special works. What a treasure. Still housed in the original wooden vitrines that were custom built for it, the permanent display is open to the public. Each individual flower is a singular work of art, but the collection as a whole is a world unto itself. A sentiment on traditional craft—in a letter from Leopold to the benefactor Mary Lee Ware: "Many people think that we have some secret apparatus by which we can squeeze glass suddenly into these forms. We have the touch. My son Rudolf has more than I have because he is my son and the touch increases in every generation.The only way to become a glass modeler of skill, I have often said to people, is to get a good great-grandfather who loved glass."

4. In a new Hilma af Klint exhibition at MoMA, What Stands Behind the Flowers is described as the output of intense engagement with nature. During the spring and summers of 1919 and 1929, Klint took up the practice of drawing flowers everyday. “I will try,” she wrote, “to grasp the flowers of the earth.” She imagines this work as a botanical atlas, representing the plants of flowers of Sweden. “I have shown,” she wrote, “that there is a connection between the plant world and the world of the soul.” Unconventional botanical drawings for the time— alongside the watercolor blooms, some of the abstract, geometric patterns and shapes she is known for—intending to connect the plant kingdom to the spiritual realm. I’m obsessed; highly recommend reading some of her writing about the spiritual life of plants. It runs through the summer; if you can’t get there before it closes Sept 29, I recommend the exhibition catalogue. I’ve just ordered my copy.

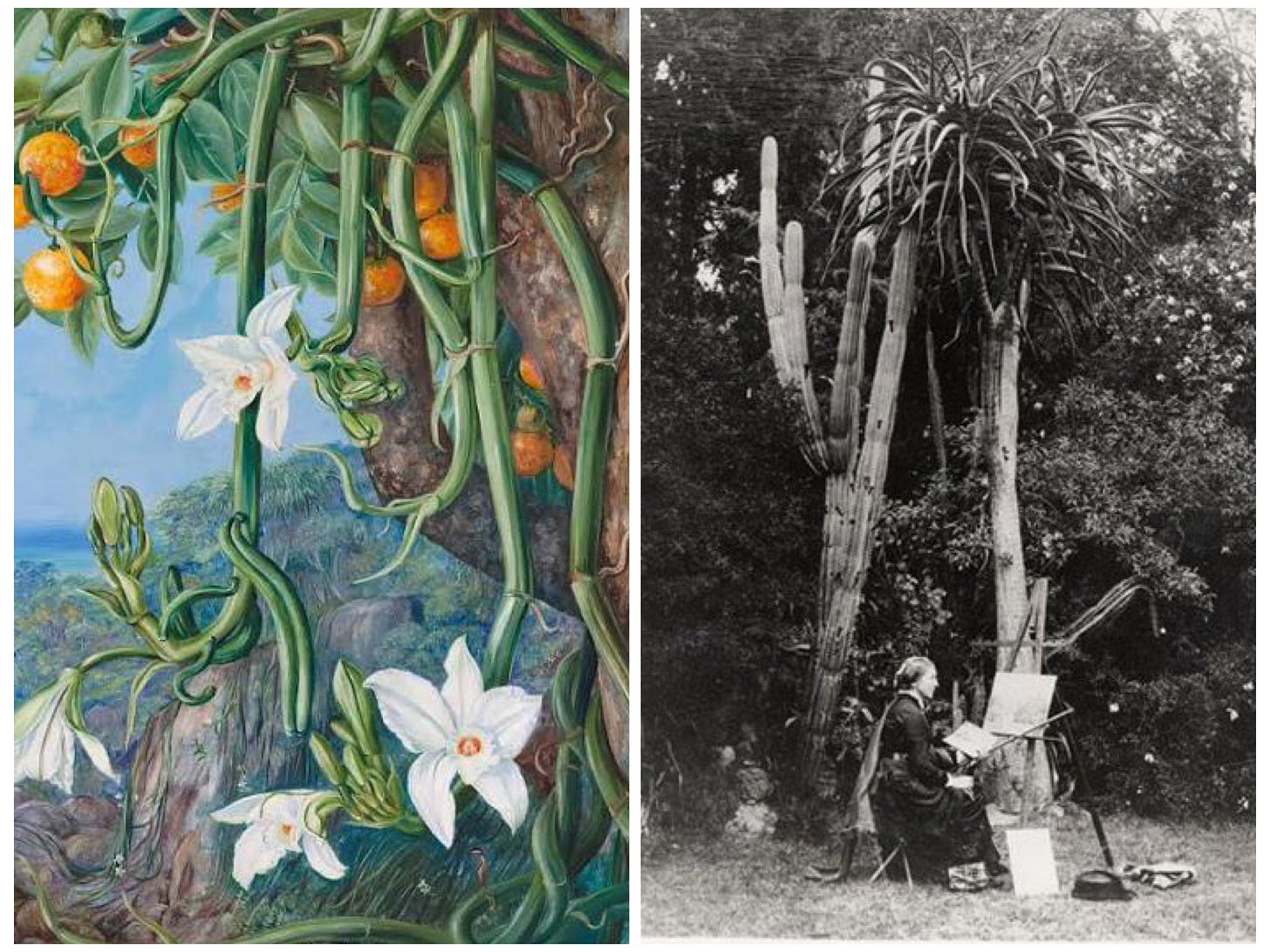

5. If you have even a passing interest in the powerhouses of the horticultural world, Kew Gardens is already on your radar. But tucked into a self-curated house gallery on the property is a collection of paintings that is every bit enchanting as the real thing. A Victorian lady traveler after our own hearts, Marianne North sold her family home after losing her father to travel the world—solo—painting the botanical life along the way. Wildflowers in India, the musk tree in Australia, Frangipani in Brazil. Over 14 years (1871-1885), Marianne traveled to 17 countries on 6 continents, setting up her easel in her Victorian dress. At the end of her life, she donated her life’s work to Kew and paid for a gallery to house the incredible collection. Together, flower after flower, a wallpaper of individually framed paintings—832 of them!—functions as a visual diary of her botanical explorations. You can read about her travels in the diary that her sister published after she died.

Love this post of In Hand. Flowers gotta love them !!!

Lisa - love your out of this world flowers!